In Daniel Pink’s classic lecture about motivation and drive for the RSA, he talks about autonomy and the desire to be self directed.

In Daniel Pink’s classic lecture about motivation and drive for the RSA, he talks about autonomy and the desire to be self directed.

In recent weeks I have been wondering about this when it comes to public transport timetables. What constraints on a person’s autonomy are going to be too burdensome, meaning a person might begin to radically change their transport behaviour as a result? And how important is the sort of transport-of-last-resort reliability function?

The bicycle and the automobile are – superficially at least – the transport modes with the greatest autonomy. Go out of the house, hop on/in, and off you go.

There are of course notable downsides and limits to that. The range and speed of a bicycle is limited, and finding a parking space and congestion when driving are major downsides. Plus if everyone does too much driving a society has a massive problem. We know all of that. Autonomy for me might mean a traffic jam in front of the house for you.

So you need public transport as the backbone of a transport system – a bus, tram, metro or train can get more people, more quickly, to their destinations. But to some extent that then is a constraint on those passengers’ autonomy. You have to wait for the next train or the next bus.

And this then is where it gets interesting.

What constraint on a person’s autonomy is too much?

This of course is going to be different depending on whether we’re looking at a person’s daily trip (usually to work), or longer journeys a person will take less often.

For daily trips, public transport timetables need to be regular enough to mean that people’s plans can change and the train can take the strain. Here let’s compare two routes – between Hermagor (popn 6824) and Villach (popn 61879) in southern Austria, and Tonnerre (popn 4381) and Auxerre (popn 34451) in Bourgogne in France.

Hermagor-Villach takes between 53 and 58 minutes by train, 41 minutes (46km) by car not including time to find a parking spot. Tonnerre-Auxerre is 42-52 minutes by train, and 37 minutes (37km) driving time, excluding time to find a parking space. In both cases both train and car ought to be options for most travellers.

But there’s a catch.

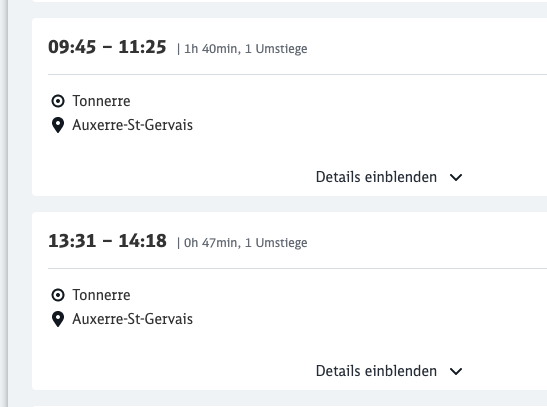

While between Hermagor and Villach there is a train each and every hour throughout the whole day, between Tonnerre and Auxerre there are major gaps in the timetable – almost 4 hours late morning with no trains (timetable excerpt shown here). The gap is 3 hours in the other direction.

While between Hermagor and Villach there is a train each and every hour throughout the whole day, between Tonnerre and Auxerre there are major gaps in the timetable – almost 4 hours late morning with no trains (timetable excerpt shown here). The gap is 3 hours in the other direction.

Someone who works in Auxerre, but lives in and their kids go to school in Tonnerre… and the kids fall ill and they need to return home at short notice? Or plans change due to an emergency of some sort? In the French case – forget it. You might be waiting hours to get home.

Timetables like this are such a constraint on a person’s autonomy that I totally understand why someone in this case buys a car. The only people who take the train between Tonnerre and Auxerre are those who have no other option – either due to financial constraints or because they are too young to drive.

By contrast Hermagor-Villach offers everyone more flexibility and more autonomy – whatever the time of day it will be maximum one hour until the next train comes (and indeed at peak hours far less than that!) so anyone can learn to rely on the train.

For longer or more occasional trips – trips that need more planning in other words – the calculation will be a different one. A passenger is going to be willing to tolerate more constraints when it comes to the regularity of the timetable, but a passenger can still – reasonably – can expect public transport to get them to their destination on the day they actually want to travel. A passenger should not have to change their mode to make a trip work.

This is a question of the get-me-there reliability of the train.

Here I have two examples of this from my #CrossBorderRail project later this summer to illustrate the point.

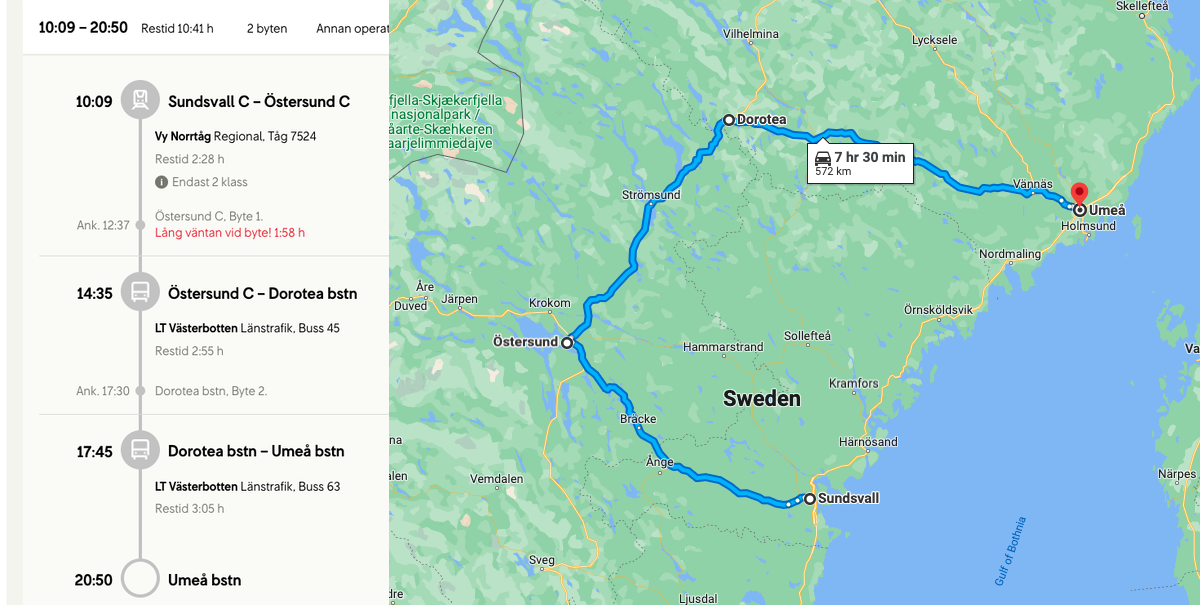

On 18th June my original plan was to travel between Trondheim in Norway and Gävle in Sweden, and then, during the night of 18th to 19th June, take the night train north to Gällivare. It was only last week – less than a month before the travel date – that it was announced that trains on Sundsvall-Umeå part of this route (the middle section) would all be cancelled – due to works somewhere near Kramfors. But Vy (that operates the night trains), SJ (that operates the daytime trains) and Trafikverket (that runs the network) are incapable of even providing a rail replacement bus for any part of the route where the train does not run, and there is no timetabled regular bus on the coastal route on the day I need to travel.

This is SJ proposes for me – with the map to show how geographically ridiculous that is:

Imagine I lived in Sundsvall and needed to take a trip to Umeå on a summer Saturday – for a wedding or a concert or something. The Swedish reaction here is basically a big shrug, and the operators pass the responsibility to each other. Here – even though my timetable is comparatively flexible, and the trip (when trains run) being something like 4 hours, the train lets me down. And the operators are incapable of offering a replacement bus or indeed any assistance of any sort.

Most people in this situation would either not make the trip, or shift to another mode. Or – if you made a trip like this comparatively often and were let down like this often – you might well consider permanently changing your behaviour (by, for example, buying a car).

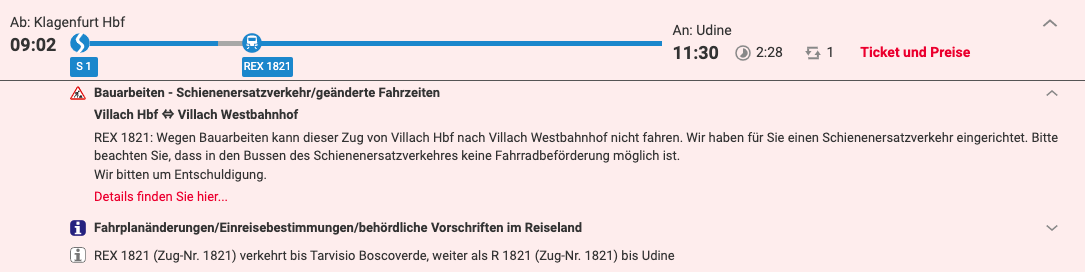

Compare this with the exemplary handling of a similar situation on Sunday 10th July, later in my trip. I would wager Klagenfurt-Udine on a Sunday morning is not a particularly popular route, but ÖBB not only informs me precisely about what is happening, but also tells me that a rail replacement bus service will be provided for me between Villach Hbf and Villach Westbahnhof. Sure, this is going to necessitate a journey time a little longer, but I know what to expect. I know it will work, and I can rely on the train + replacement bus combination.

The crux then is this: if we are to encourage modal shift for longer distance journeys, be they daily or occasional, timetables need to be able to allow a person to retain their autonomy. For a person’s plans to change, and the next train still to be there soon enough. And – especially in the case of longer distance journeys – the train needs to be able to get you there, even in the case of disruptions.

These things ought to be basic, but as the French and Swedish examples here show, it seems that basic understanding is still missing in parts of Europe.

This is why it’s so difficult to persuade people to abandon their car. Even if you can do 90% of your journeys by public transport, there’s that last 10% that’s hard or impossible. And once that car is paid for, and waiting outside, it’s so much easier and cheaper to reach for the car keys than the extra effort of going through the above hassle with public transport.

That’s the reason above all, that we need to use the new technologies to create a universal transport on demand service – a taxi-bus – that is door-to-door and fits around your time needs, like a car or taxi, but shared, like a bus or train, to reduce the cost and the traffic, and to make it greener. Taxis are too expensive to do that now for most people and most journeys. And they’re not always convenient, and they don’t handle peaks well.

The technologies I’m talking about are a combination of IT to book, schedule, integrate and price journeys, and at some point, autonomous vehicles to remove the cost of the driver and the parking problem.

If we could just say “Alexa, get 3 people and 2 bags to x before hh:mm, and I’m happy to share” and KNOW that it would always work at moderate cost, then we could seriously think about selling our cars.

In the short term, it might be just to bridge the gaps in public transport exposed above. But eventually, as autonomous cars catch on, and if we do it right, it could replace conventional scheduled bus & train services.

I can foresee a future debate about concreting over the railways, because door-to-door taxi-buses would use the scarce real estate better, cheaper, and greener.

I wish I could believe in that. But I don’t! A taxi on demand is still going to have the same peak hours problems that cars have (and the associated traffic).

As the Austrian example here shows: you can make this work. Now. Just a bunch of railway systems don’t do the basics right…